State Management in Godot with a Vue.js Twist

I’m always trying to improve the way I manage communication between nodes and scenes in my Godot games, and recently I came up with a solution based on an experiment I did while studying Vue.js. So I decided to write this text to demonstrate the concept.

Once again, this is not about ECS™

First of all, this text is not strictly about design patterns or system architectures. I’m a systems analyst and I know that design patterns and system architectures are important, but I don’t like to talk about them in an idealistic way, especially in game development.

Overthinking patterns and architectures in game development is counterproductive. Games are mostly designed and built by prototyping, so you need fast and refactorable development, not extensive analysis, UML diagrams, etc.

So I’m not going to spit out any random acronyms like ECS or any other fancy names, because that would just add unnecessary complexity, and because this is all about how I do things in my own game projects.

The problem

Having worked with games for a number of years, I can say one thing for sure: global state management is difficult.

Both Godot and Unity make this easier by implementing features that modularise the game, such as prefabs, components, tree structures and event systems, so that you can break the logic down into small, independent elements.

This helps a lot, especially in Godot, which makes it even easier by allowing you to edit multiple scenes (prefabs) at the same time.

But it also has its own problems and limitations. The more you modularise your game, the more you need to propagate signals (events) through the scene tree, because some state updates need to reach elements that are “further away” in the scene tree.

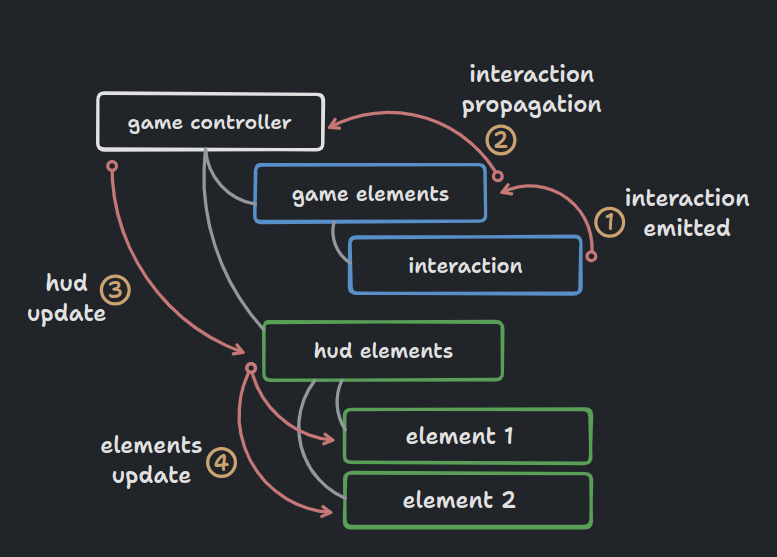

So this is basically how I used to make my games:

As I said before, games are mostly designed and built by prototyping, so eventually you will find that your game gets bigger and bigger and simply propagating the signals through the scene tree becomes more and more difficult as many elements end up depending on more data from multiple sources.

Here comes the infamous Singleton

Singletons (Autoloads in Godot) and static classes are just magic. They solve all the problems of referencing data from multiple sources by centralising everything in one global object.

Except that they actually create more problems:

- You lose editor integration because singletons and static classes are only accessible through code.

- Tracking data dependencies is much harder, because you can only track them in code.

- You lose almost all the benefits of modularity, as everything now depends on global static objects.

- Refactoring elements is more difficult because you have lost modularity.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against using singletons. It’s perfectly acceptable to use singletons if your game is just too simple, or if you just need to get it done in a short time. Also, singletons are really useful for things that really need to run throughout the game, like a music manager, a scene transition manager, a savegame manager, etc.

So singletons are perfectly fine, but if you want something more stable, modular and refactorable, it’s better to avoid them and try something else.

The solution (for now)

So, after years of struggling, I have finally found a sweet spot when it comes to global state management.

I strongly believe in the potential of project-based learning, so I often use new projects or small experiments as an opportunity to learn or try something new.

Some time ago I learnt the basics of Vue.js (a web framework) on these small experiments, and recently I started a new Godot project, which happened to be the kind that requires a lot of state sharing, so I had the idea to mix Godot with some Vue.js concepts.

Vue.js Stores

One of the main concepts of Vue.js is state management.

It uses events on data updates so that the UI elements are automatically updated when needed.

In Godot, this is equivalent to using setget and emitting signals in the setter methods.

So nothing new here.

But this only applies to local states, when it comes to global states you end up with the same propagation problem mentioned above.

Vue.js also has this limitation, so they try to solve it with a “store”.

Quoting their own documentation to summarise the concept:

A Store is an entity holding state and business logic that isn’t bound to your Component tree. In other words, it hosts global state. It’s a bit like a component that is always there and that everybody can read off and write to.

A store should contain data that can be accessed throughout your application. This includes data that is used in many places, e.g. User information that is displayed in the navbar, as well as data that needs to be preserved through pages, e.g. a very complicated multi-step form.

It sounds similar to singletons, but it’s a bit different (and it’s not ECS, even though they use the term “component”). While singletons tend to centralise everything, stores are much more modular, as you can split all states into multiple stores without running into the propagation problem or other problems associated with singletons.

Godot State Resources

It makes more sense to explain it in Godot terms.

All assets imported/used in Godot projects are based in the Resource class.

This means that anything that can be saved as a file in the project is a resource.

And you can create your own custom resources by extending the Resource class when writing scripts.

If you have never heard of custom resources in Godot (or ScriptableObjects in Unity), I suggest you stop here and read about them first.

I recommend this GDQuest video tutorial: Godot RPG Character Stats Tutorial: Godot Open RPG

And also this docs page: Creating your own resources

The trick starts here

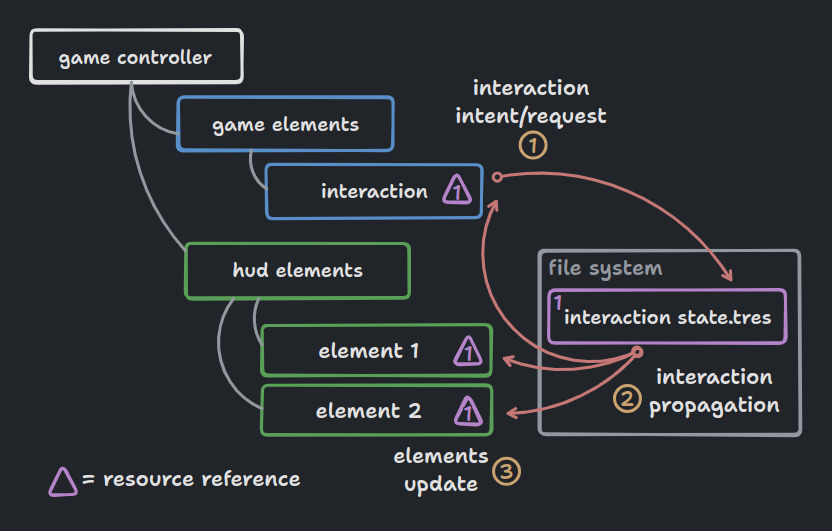

Because Godot resources are unique at runtime, no matter how you load a resource, it will always point to the same object reference, so you can load it multiple times and change its properties and connect to its signals as if it were a global object (as long as there is at least one reference to it).

So what I did was implement the “stores” concept using custom resources:

Since this example only has a single state, it’s not so clear how it’s different or more modular than a singleton, so I’ve also made a simple project to demonstrate the concept.

In this demonstration, I have created 4 state resources:

- Click State: Emits and counts clicks

- Shop State: Manages values related to the Click Shop, such as batch amount and selling price

- Cash State: Manages the amount of cash (received after selling clicks)

- Upgrade State: Manages upgrades, such as click amount increase and auto-clicker

The amount and structure of state resources are entirely up to you.

Feel free to check out this project on my GitHub.

State Resources vs Singletons

When it comes to its advantages over singletons:

- You preserve editor integration, as resources are accessible in the editor via

@exportvariables (except for signals, which still need to be connected via code). - Tracking data dependencies is easier, as Godot has tools to track resource dependencies and ownership.

- You preserve modularity because resources are independent files.

- Refactoring elements is easier because data is only attached to objects that depend on it.

- Plus: you can edit states at runtime for testing purposes (using

@exportandsetgeton state variables). - Plus²: you can reuse the same state resource class (similar to the

ButtonGroupresource).

That’s all

Thanks for reading, I hope this has helped in some way.

If you are interested in exploring the concepts in more depth, you can search for Observer Pattern and Reactive Programming.

As for other web frameworks, there are also React.js and Angular.js (though I have not used either, only Vue.js).

There’s also a Reactive Programming library for Godot called GodotRx, but it’s only available in C#, and it’s more complex than what I did using the custom resources, as I only used certain parts of the concept.

Comments